1

She left the refuge in a meteorological rover from the previous century, a high square thing with a luxurious window-box driver’s compartment up top. It was not unlike the front half of the expedition rover in which she had first traveled to the North Pole, with Nadia and Phyllis and Edmund and George. And because she had spent thousands of days since then in such machines, she at first had the impression that what she was doing was ordinary, contiguous with the rest of her life.

But she drove northeast, downcanyon, until she was in the bed of the little unnamed channel at sixty degrees longitude, fifty-three degrees north. This valley had been carved by a small aquifer outbreak during the late Amazonian, running in an earlier graben fault, down the lower slopes of the Great Escarpment. The scoring effects of the flood were still visible on the rims of the canyon walls, and in the lenticular islands of bedrock on the floor of the channel.

Which now ran north into a sea of ice.

• • •

She got out of the car wearing a fiberfilled windsuit, a CO2 mask, goggles, and heated boots. The air was thin and cold, though it was spring now in the north— Ls 10, m-53. Cold and windy, ragged lines of low puffy clouds racing east. It was either going to be an ice age or, if the greens’ manipulations forestalled it, then a year-without-summer, like 1810 on Earth, when the explosion of the volcano Tambori had chilled the world.

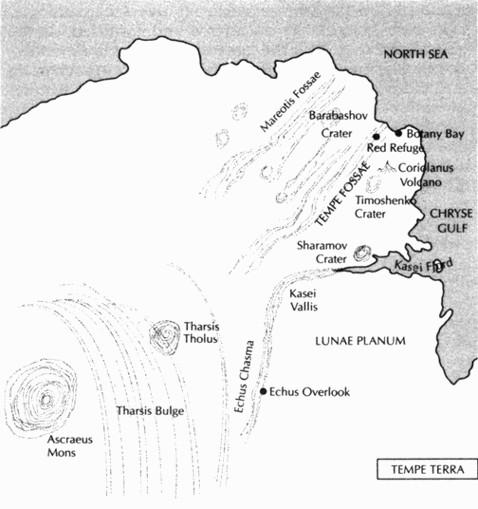

TEMPE TERRA

She walked the shore of the new sea. It was at the foot of the Great Escarpment, in Tempe Terra, a lobe of ancient highlands extending into the north. Tempe had probably escaped the general stripping of the northern hemisphere by being roughly opposite the impact point of the Big Hit, which most areologists now agreed had struck near Hrad Vallis, above Elysium. So; battered hills, overlooking an ice-covered sea. The rock looked like a red sea’s surface in a wild cross chop; the ice looked like a prairie in the depths of winter. Native water, as Michel had said— there from the beginning, on the surface before. It was a hard thing to grasp. Her thoughts were scattered and confused, darting this way and that, all at the same time— it was like madness, but not. She knew the difference. The hum and keen of the wind did not speak to her in the tones of the MIT lecturer; she suffered no choking sensations when she tried to breathe. It was not like that. Rather her thinking was accelerated, fractured, unpredictable— like that flock of birds over the ice, zigzagging across the sky in a hard wind from the west. Ah the feel of that same wind against her body, shoving at it, the new thick air like a great animal paw. . . .

The birds struggled in it with reckless skill. She stood for a while and watched: they were skuas, out hunting over dark streaks of open water. These polynyas were just the surface signs of immense pods of liquid water under the ice; she had heard that a continuous channel of under-ice water now wrapped the globe, winding east over old Vastitas, tearing frequent polynyas in the surface, gaps which then stayed liquid for an hour or a week. Even with the air so cold, the underwater temperatures were warmed by the drowned Vastitas moholes, and rising heat from the thousands of thermonuclear explosions set off by the metanats around the turn of the century. These bombs had been placed deep enough in the megaregolith to trap their radioactive fallout, supposedly, but not their heat, which rose in a thermal pulse through the rock, a pulse that would continue for years and years. No; Michel could talk about it being Mars’s water, but there was little else that was natural about this new sea.

Ann hiked up a ridge to get a wider view. There it lay: ice, mostly flat, sometimes shattered. All as still as a butterfly on a twig, as if the whiteness might suddenly lift off and fly away. The birds’ wheeling and the clouds’ scudding showed how hard the wind blew, everything in the air pouring east; but the ice remained still. The wind’s voice was deep and huge, scraping over a billion cold edges. A strip of gray water was striated by windchop, the strength of each gust precisely registered by the flayed cat’s paws, each brush of harder wind feathering the larger waves with exquisite sensitivity. Water. And below that brushed surface, plankton, krill, fish, squid; she had heard they were producing in hatcheries all the creatures of the extremely short Antarctic food chain, and then releasing them to the sea. Teeming water.

The skuas wheeled overhead. One cloud of them whirlpooled down onto something along on the shore, behind some rocks. Ann hiked toward them. Suddenly she saw the birds’ target, lying in a cleft at the edge of the ice: the mostly eaten remains of a seal. Seals! The corpse lay on tundra grass, in the lee of a patch of sand dunes, sheltered by another rocky ridge running down into the ice. The white skeleton emerged from dark red flesh, ringed by white blubber, black fur. All torn open to the sky. Eyes pecked out.

She hiked on past the corpse, up another little ridge. The ridge made a kind of cape extending into the ice, and beyond it was a bay. A round bay— a crater, infilled by ice. It had happened to lie at sea level, had happened to have a breach in its rim on its seaward side, so that water and ice had poured in and filled it. Now a round bay, perfect for a harbor. One day it would be a harbor. About three kilometers across.

Ann sat down on a boulder on the cape, and looked out at the new bay. Her breath heaved in and out of her in an involuntary motion, her rib cage moving violently, as during labor contractions. Sobs, yes. She pulled aside her face mask, blew her nose using her finger, wiped her eyes, all the while still weeping furiously. This was her body. She recalled the first time she had stumbled onto the flooding of Vastitas, in a solo trip ages ago. That time she had not cried, but Michel had said that was only shock, the numbness of shock, as in any injury— withdrawal from her body and her feelings. Michel would call this response healthier, no doubt, but why? It hurt— her body, spasming in a seismic trembling. But when it was over, Michel would say, she would feel better. Drained. A tension gone— the tectonics of the limbic system— she scorned such simplistic analogies as Michel offered, the woman as planet, it was absurd. Nevertheless there she sat, sniffling, looking out at the ice bay under scudding clouds, feeling drained.

• • •

Nothing moved except for clouds overhead, and cat’s paws on a patch of open water, gust after gust, shimmering gray, mauve, gray. Water moved but the land was still.

Finally Ann stood and walked down a rib of hard old shishovite, now forming a narrow divide between two long beaches. To tell the truth, above the ice there was not that much that had changed from the primal state. Down at the waterline it was a different story. Here the daily trade winds over the open water of the summer bay had created waves large enough to break the remaining chunks of ice into what they called brash ice. Lines of this flotsam were now beached above the current ice level, like ice sculptures depicting driftwood. But in the summer this ice had helped to rip up the sand of the new beaches, tearing it into a slurry of ice and mud and sand, now frozen in place like brown cake frosting.

Ann walked slowly across this mess. Beyond it there was a little inlet, crowded with ice boulders that had grounded in the shallows and then been frozen into the sea surface. Exposure to sun and wind had rendered these boulders into baroque fantasias of clear blue ice and opaque red ice, like aggregates of sapphire and bloodstone. The south sides of the blocks had melted preferentially, the meltwater frozen in icicles, ice beards, ice sheets, ice columns.

Looking back at the shore she saw again how the sand was furrowed and torn; the damage was terrific, the gouges sometimes two meters deep— incredible force, to plow such trenches! The sand drifts must have been loess, made of loose light aeolian deposits. Now a no-man’s-land of frozen mud and dirty ice, as if bombs had devastated some sad army’s trenches.

She continued outward, stepping on opaque ice. On the surface of the bay. Like a world covered in semen. Once the ice cracked under her boot.

When she was well out on the bay she stopped and had a look around. Tight horizons indeed; she climbed a flat-topped berg, which gave her a larger view over the expanse of ice, out to the circle of the crater rim, just under the running clouds. Though cracked and jumbled and lined by pressure ridges, the ice nevertheless clearly conveyed the flatness of the water beneath it. To the north the gap to the sea was obvious. Tabular bergs stuck out from the ice like deformed castles. A white waste.

After struggling to come to grips with the scene, and failing, she clambered off the berg and hiked back to the shore, then back toward her car. As she was crossing the little ridge cape, movement down at the edge of the ice caught her eye. A white thing moved— a person in a white walker, on all fours— no. A bear. A polar bear. Walking along the edge of the ice.

It spotted the dust devil of skuas over the dead seal. Ann crouched behind a boulder, went prone on a patch of frosty sand. Cold all along the front of her body. She looked over the boulder.

The bear’s ivory fur yellowed on its flanks and legs. It raised a heavy head, sniffed like a dog, looked around curiously. It shambled to the corpse of the seal, ignoring the column of squealing birds. It ate from the seal like a dog from a bowl. It raised its head, muzzle dark red. Ann’s heart pounded. The bear sat on its haunches and licked a paw, rubbed its face until it was clean, catlike in its fastidiousness. Then without warning it dropped to all fours and started up the slope of rock and sand, toward Ann’s hiding place behind the boulder. It trotted, moving both the legs on one side of its body in the same motion, left, right, left.

Ann rolled down the other side of the little cape and got up and ran up the trough of a shallow fracture, leading her southwest. Her rover was almost directly west of her, she reckoned, but the bear was coming from the northwest. She clambered up the short steep side of the southwest-trending canyon, ran over a strip of high ground to another little fracture canyon, trending a bit more to the west than the previous one. Up again, onto the next strip of high ground between these shallow fossae. She looked back. Already she was panting, and her rover was still at least two kilometers away, to the west and a little south. It was still out of sight, behind ragged hillocks. The bear was north and east of her; if it made directly for the rover it would be almost as close to it now as she was. Did it hunt by sight or by smell? Could it plot the course of its prey, and move to cut it off?

No doubt it could. She was sweating inside her windsuit. She hustled down into the next canyon and ran in it for a while, west southwest. Then she saw an easy ramp and ran up to the next intercanyon strip, a kind of wide high road between the shallow canyons on both sides. Looking back she found herself staring at the polar bear. It stood on all fours, behind and two canyons over, looking like a very big dog, or a cross between a dog and a person, draped in straw-white fur. It amazed her to see such a creature out there, the food chain couldn’t possibly support such a large predator, could it? They must surely be feeding it at feed stations. Hopefully so, or else it would be very hungry. Now it dropped into the canyon two over, out of sight, and Ann started to run down the strip toward her rover. Despite her running around, and the tight rugged horizon, she was confident of her sense of the car’s location.

She kept to a pace she thought she could sustain for the whole distance. It was hard not to let loose and sprint at full speed, but no, no, that would lead to a collapse eventually. Pace yourself, she thought, gasping in short pants. Get down off the high ground into a graben so you’re out of sight. Keep oriented, are you passing south of the rover? Back up to the higher ground, for just a moment to look. There behind that low flat-topped hill, which was a small crater, with a hump on the south end of the rim— she was certain— though the rover was still out of sight, and the jumbled land was easy to get confused in. A thousand times she had gotten briefly semilost, unsure of her exact location in relation to some fixed point, usually her parked rover— not a big deal usually, as her wrist’s APS could always lead her back. As it could now too, but she was sure it was over there behind that bump of a crater.

The cold air burned in her lungs. She recalled the emergency face mask in her backpack, and stopped and yanked off the backpack and dug, pulled off the CO2 mask and put on the air mask; it contained a short supply of compressed oxygen in its frame, and with it pulled over her mouth and nose and turned on, she was suddenly stronger, faster, could hold a better pace. She ran along a strip of high ground between canyons, hoping to get a sighting of the rover round the slope of the crater apron. Ah, there it was! Panting triumphantly she sucked down the cool oxygen; it tasted lovely, but was not enough to stop her gasping. If she went down into the trough to her right it looked like it would run straight to the rover.

She glanced back and saw the polar bear running too, legs now in a shambling kind of gallop— lumbering— but it ate up the ground with that run, and the shallow canyon walls seemed no impediment to it, it flowed over them like a white nightmare, a thing beautiful and terrifying, the liquid flow of its muscles loose under thick yellow-tipped white fur. All this she saw in a single moment of the utmost clarity, everything in her field of vision distinct and acute and luminous, as if lit from within. Even running as hard as she could, focusing on the ground to make sure she didn’t trip over anything, she still saw the bear flowing over the red slope, like an afterimage. Pounding, running hard, boulder ballet; the bear was fast and the terrain nothing to it, but she too was an animal, she too had spent years in the back country of Mars, many more years in fact than this young bear, and she could run like an ibex over the terrain, from bedrock to boulder to sand to rubble, pushing hard but perfectly balanced, in control of the dash and running for her life. And besides the rover was near. Just up one last canyon side, and the slope of the apron, and there it was, she almost ran into it, stopped, reared up and pounded the curved metal side with a hard triumphant wham, as if it were the bear’s snout, and then with a second more controlled punch to the lock door console she was inside, inside, and the outer-lock door closed behind her.

She hurried upstairs to the driver’s aerie to look back. Through the glass she saw the polar bear below, inspecting her vehicle from a respectful distance. Out of dart-gun range, sniffing thoughtfully. Ann was sweating hard, still gasping hard for air, in and out, in and out— what violent paroxysms the rib cage could go through! And there she was, sitting safe in the driver’s seat! She only had to close her eyes and she saw again that heraldic image of the bear flowing over the rock; but open them and there the dashboard gleamed, bright and artificial and familiar. Ah so strange!

• • •

She was still in a kind of shock a couple of days later, able to see the polar bear if she closed her eyes and thought about it; distracted. By night the ice in the bay boomed and groaned, sometimes cracked explosively, so that she dreamed of the assault on Sheffield, groaning herself. By day she drove so carelessly that she had to put the rover on automatic pilot, instructing it to make its way along the shore of the crater bay.

While it rolled she wandered around the driver’s compartment, her mind racing. Out of control. Nothing to be done but laugh and endure it. Strike the walls, stare out the windows. The bear was gone but it wasn’t. She looked it up: Ursus maritimus, ocean bear; the Inuit called it Tôrnâssuk, “the one who gives power.” It was like the landslide that had almost caught her in Melas Chasma, now a part of her life forever. Facing the landslide she had not moved a muscle; this time she had run like hell. Mars could kill her, no doubt it would kill her, but no big zoo creature from Earth was going to kill her, not if she could help it. Not that she was so enamored of life, far from it; but one should be free to choose one’s death. As she had chosen in the past, twice at least. But Simon and then Sax— like little brown bears— had snatched her death away from her. She still didn’t know what to make of that, how to feel about it. Her mind was racing so fast. She held on to the back of the driver’s seat. Finally she reached forward and punched Sax’s old First Hundred number on the rover’s screen keyboard, XY23, and waited for the AI to route the call to the shuttle returning Sax and the others to Mars; and after a while there he was, with his new face, staring into a screen.

“Why did you do it?” she shouted. “It’s my death to choose as I please!”

She waited for the message to reach him. Then it did and he jumped, the image of him jiggled. “Because—” he said, and stopped.

Ann felt a chill. That was just what Simon had said, after he had pulled her back in out of the chaos. They never had a reason, only life’s idiot because.

Sax went on: “I didn’t want— it seemed like such a waste— what a surprise to hear from you. I’m glad.”

“To hell with that,” Ann said.

She was about to cut the connection when he started speaking again— they were in simultaneous transmission now, alternating messages, “It was so I could talk to you, Ann. I mean it was for myself— I didn’t want to be missing you. I wanted you to forgive me. I wanted to argue with you more and— and make you see why I’ve done what I’ve done.”

His chatter stopped as abruptly as it had started, and then he looked confused, even frightened. Perhaps he had just heard “To hell with that.” She could scare him, no doubt of that.

“What crap,” she said.

After a while: “Yes. Um— how are you doing? You look. . . .”

She cut the connection. I just outran a polar bear! she shouted in her mind. I was almost eaten by your stupid games!

No. She wouldn’t tell him. The meddler. He had needed a good referee for his submissions to The Metajournal of Martian History, that was what it came down to. Making sure his science was properly peer-reviewed— for that he would crash around in a person’s most inward desires, in her essential freedom to choose life or death, to be a free human being!

At least he hadn’t tried to lie about it.

And— well— here she was. Rage; remorse without cause; inexplicable anguish; a strangely painful exhilaration: all this filled her at once. The limbic system, vibrating madly, spiking every thought with contradictory wild emotions, disconnected from the thoughts’ content: Sax had saved her, she hated him, she felt a fierce joy, Kasei was dead, Peter wasn’t, no bear could kill her, etc.— on and on and on. Oh so strange!

• • •

She spotted a little green rover, perched on a bluff over the ice bay. Impulsively she took over the wheel and drove up to it. A little face peered out at her; she waved through the windshields at it. Black eyes— spectacles— bald. Like her stepfather. She parked her rover next to his. The man gestured for her to come over, holding up a wooden spoon. He looked vague, only half pulled out of his own thoughts.

Ann put on a down jacket and went through the lock doors and walked between the cars, feeling the shock of the frigid air like a dousing in cold water. It was nice to be able to walk between one rover and another without suiting up, or, to get to the crux of the matter, risking death. Amazing that more people hadn’t been killed by carelessness or lock malfunction. Some had been, of course. Scores, probably, if you added them all up. Now it was just a dash of cold air.

The bald man opened his inner-lock door. “Hello,” he said, and offered a hand.

“Hello,” Ann said, and shook it. “I’m Ann.”

“I’m Harry. Harry Whitebook.”

“Ah. I’ve heard of you. You design animals.”

He smiled gently. “Yes.” No shame; no defensiveness.

“I was just chased by one of your polar bears.”

“Were you!” His eyes opened round. “Those are fast!”

“So they are. But they’re not just polar bears, are they.”

“They’ve got some grizzly genes, for altitude. But mostly it’s just Ursus maritimus. They’re very tough creatures.”

“A lot of creatures are.”

“Yes, isn’t it marvelous? Oh excuse me, have you eaten? Would you like some soup? I was just making soup, leek soup, I guess it must be obvious.”

It was. “Sure,” Ann said.

• • •

Over soup and bread she asked him questions about the polar bear. “Surely there can’t be a whole food chain here for something that huge?”

“Oh yes. In this area there is. It’s well-known for that— the first bioregion robust enough for bears. The bay is liquid to the bottom, you see. The Ap mohole is at the center of the crater, so it’s like a bottomless lake. Iced over in winter of course, but the bears are used to that from the Arctic.”

“The winters are long.”

“Yes. The female bears make dens in the snow, near some caves in dike outcroppings to the west. They don’t truly hibernate, their body temperatures drop just a few degrees, and they can wake up in a minute or two, if they need to adjust the den for heat. So they den for as much of the winters as they can, then live in there and forage out till spring. Then in spring we tow some of the ice plates through the mouth of the bay out to sea, and things develop from there, bottom to top. The basic chains are Antarctic in the water, Arctic on the land. Plankton, krill, fish and squid, Weddell seals, and on land rabbits and hares, lemmings, marmots, mice, lynx, bobcat. And the bears. We’re trying with caribou and reindeer and wolves, but there isn’t the forage for ungulates yet. The bears have been out just a few years, the air pressure hasn’t been adequate until recently. But it’s a four-thousand-meter equivalent here now, and the bears do very well with that, we find. They adapt very quickly.”

“Humans too.”

“Well, we haven’t seen too much at the four-thousand-meter level yet.” He meant four thousand meters above sea level on Earth. Higher than any permanent human settlement, as she recalled.

He was going on: “ . . .eventually see thoracic-cavity expansion, bound to happen. . . .” A man who talked to himself. Big, bulky; white fur in a fringe around his bald pate. Black eyes swimming behind round spectacles.

“Did you ever meet Hiroko?” she said.

“Hiroko Ai? I did, once. Lovely woman. I hear she’s gone back to Earth, to help them adapt to the flood. Did you know her?”

“Yes. I’m Ann Clayborne.”

“I thought so. Peter Clayborne’s mother, isn’t that right?”

“Yes.”

“He’s been in Boone recently.”

“Boone?”

“That’s the little station across the bay. This is Botany Bay, and the station is Boone Harbor. A kind of joke. Apparently there was a similar pairing in Australia.”

“Indeed.” She shook her head. John would be with them forever. And by no means the worst of the ghosts haunting them.

As for instance this man, the famous animal designer. He clattered about the kitchen, pawing at things shortsightedly. He put the soup before her and she ate, watching him furtively as she did. He knew who she was, but he did not seem uncomfortable. He did not try to justify himself. She was a red areologist, he designed new Martian animals. They worked on the same planet. But that did not mean they were enemies, not to him. He would eat with her without malice. There was something chilling in that, overbearing despite his gentle manner. Obliviousness was so brutal. And yet she liked him; that dispassionate power, vagueness— something. He bumbled around his kitchen, sat and ate with her, quickly and noisily, his muzzle wet with the clear soup stock. Afterward they broke pieces of bread from a long loaf. Ann asked questions about Boone Harbor.

“It has a good bakery,” Whitebook said, indicating the loaf. “And a good lab. The rest is just an ordinary outpost. But we took the tent down last year, and now it is very cold, especially in the winter. Only forty-six degrees latitude, but we feel it as a northern place. So much so that there is some talk of putting the tent back up, in winter at least. And there are people who say we should leave it on until things warm up.”

“Till the ice age is over?”

“I don’t think there will be an ice age. This first year without the soletta was bad, of course, but various compensations ought to be possible. A cold couple of years, that’s all it will be.”

He waggled a paw: it could go either way. Ann almost threw her chunk of bread at him. But best not to startle him. She controlled herself with a shudder.

“Is Peter still in Boone?” she asked.

“I think so. He was a few days ago.”

They talked some more about the Botany Bay ecosystem. Without a fuller array of plant life, animal designers were sharply limited; it was still more like the Antarctic than the Arctic in that respect. Possibly new soil-enhancement methods could speed the arrival of higher plants. Right now it was a land of lichen, for the most part. The tundra plants would follow.

“But this displeases you,” he observed.

“I liked it the way it was before. All Vastitas Borealis was barchan dunes, made of black garnet sand.”

“Won’t some remain, up next to the polar cap?”

“The ice cap will go right down to the sea line in most places. As you say, kind of like Antarctica. No, the dunes and the laminate terrain will be underwater, one way or another. The whole northern hemisphere will be gone.”

“This is the northern hemisphere.”

“A highland peninsula. And it’s gone too, in a way. Botany Bay was Arcadia Crater Ap.”

He looked at her through the spectacles, peering. “Perhaps if you lived at high altitude, it might seem like the old days. The old days, with air.”

“Perhaps,” she said cautiously. He was circling the chamber, shambling about with heavy steps, cleaning big kitchen knifes at the sink. His fingers ended in short blunt claws; even clipped they made it hard for him to work with small objects.

She stood up carefully. “Thanks for dinner,” she said, backing toward the lock door. She grabbed her jacket on the way out and slammed the door on his look of surprise. Out into the hard cold slap of the night, into her jacket. Never run away from a predator. She walked back to her car and climbed in without looking back.